While rare, serious illness linked to Covid-19 in children has researchers studying variants.

Pediatric researchers are investigating whether Covid-19 is becoming more severe for children now that variants are causing localized flare-ups, even as U.S. cases overall decline.

By early April, the rate of Covid-19 cases in young kids and early teens began surpassing that of those 65 and older, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The latest CDC data suggest the trend is continuing. At the same time, hospitalizations for children with Covid-19 aren’t falling as much as for those 18 and up. That has researchers concerned that variants may be affecting youths in new ways, including a rare inflammatory disease that has been linked to Covid-19 infection.

“The big concern is that we’ve left a whole population of children unprotected,” said Adrienne Randolph, a critical-care doctor at Boston Children’s Hospital who is leading the CDC-funded research.

Cases of the rare disease, called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, totaled more than 2,000 in February and surpassed 3,000 by April 1, according to the CDC, which will soon update its tally.

Vaccine manufacturers’ clinical trials have mostly focused on adults, and now almost 72% of those 65 and older are fully inoculated, according to the CDC. Meanwhile, young children don’t yet have access to shots, and companies are still studying the effects on them. Pfizer Inc.’s vaccine has been available for teens 16 and older, and won authorization Monday for ages 12 to 15.

The vaccines have been found to work well in adults against the current virus mutations, including the B.1.1.7 variant identified in the U.K. Still, pockets of unvaccinated people are giving the variant room to spread, which may be especially worrisome for children. That variant, which is more contagious than the original virus, became the most dominant strain in the U.S. in early April and now makes up almost 60% of cases, according to the CDC.

In Colorado, which has one of the country’s highest infection rates, Sam Dominguez, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Colorado, started to see an increase in cases of the rare inflammatory disease at the end of April.

Like the rest of the country, Colorado saw a surge in Covid-19 cases between November and February. Cases started ticking up again last month. B.1.1.7 is the dominant variant.

“We’re watching it very carefully,” Dominguez said. “I think that’s a really important question: Does B.1.1.7 cause more MIS-C?”

“Mortality, thankfully, is low but that doesn’t mean there’s not morbidity,” Randolph said. “Some have go to rehab, some go home on oxygen.”

Randolph had been studying MIS-C and severe Covid-19 as part of an earlier study backed by $2.1 million from the CDC. The work was renewed May 4 and will look at whether the virus is taking a bigger toll on children, Randolph said.

She plans to go back through data over the past few months as she and her team collect new reports — some 50 pages long — from a nationwide network of pediatric health centers. If they find worrisome patterns, they’ll “report findings as soon as we can,” she said.

Randolph has found that children with severe Covid-19 tend to have underlying conditions that make them susceptible, just like adults. But pediatric MIS-C patients tend to be healthy and without Covid-19 symptoms. The study will also examine vaccine effectiveness in children.

“The question is, what is B.1.1.7 going to do in the many states that are out there with lower vaccination rates? And we just don’t know that,” said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, who also advised President Joseph Biden on Covid-19 during his transition.

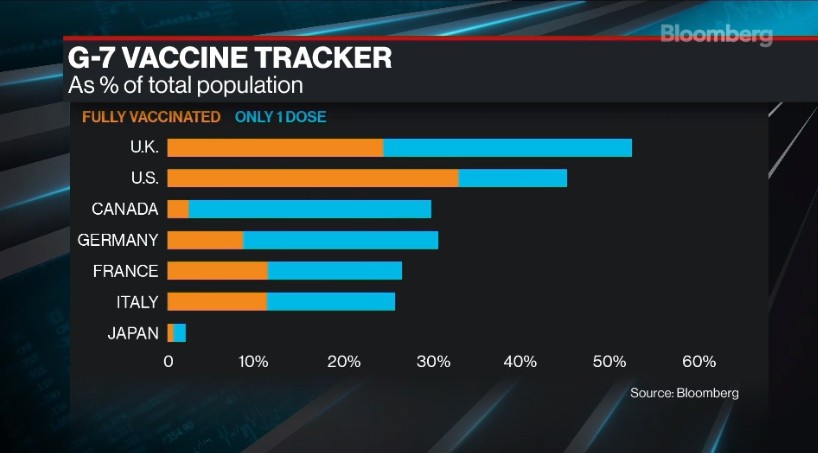

Children may be more vulnerable in states with low vaccination rates. Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Wyoming and Idaho are the five worst-performing when measured by percent of population with at least one shot, according to the Bloomberg Vaccine Tracker. Most aren’t seeing a rise in cases currently. That could change.

“Last summer, we saw a huge surge in cases in these Southern states, likely tied to people going into air conditioning in the hot summer months,” said Megan Ranney, an emergency physician and researcher at Brown University in Rhode Island. “If vaccination rates do not increase, it is likely there will be recurrent surges.”

The risk for kids will likely come from afterschool programs and seeing their friends, rather than classroom activities themselves, she said.

“When kids go back to school, they also go back to socializing, the extracurricular activities” Ranney said. “In those situations, they’re often not masked, not in well-ventilated spaces.”